Back to Hamilton: An American Musical (Original Broadway Cast Recording)

Mr. President, you asked to see me?

This exchange hearkens back to Hamilton’s first meeting with Washington in the show during “Right Hand Man” (“Your excellency, you wanted to see me?”) Of course, the dynamic between the two men has changed, and this is now their last meeting.

This is echoed in the opening of “We Know”. Hamilton enters stage, addressing someone by their title and the same piano plays in the background.

[WASHINGTON]

Washington’s voice is noticeably higher in this early section—he is weary. After all, he did not run for president; he was requested by popular demand. Later in the song, when he gets home, he is joyous.

I know you’re busy ⮐

⮐

[HAMILTON] ⮐

What do you need, sir?

Angelica says a similar phrase in “Take a Break”, “I know you’re very busy”, and Alexander still dismisses her request to spend time with him and the family. However here, Washington says the same and Hamilton gives him his full attention, even going as far as to repeat himself to hurry Washington’s request. This contrast shows Hamilton’s dedication to his work over his family.

I wanna give you a word of warning

Comic wordplay: Hamilton thinks “warning” means “cautionary advice” (he thinks he’s in hot water) whereas Washington simply means “advance notice” (of his resignation).

But it also means ‘cautionary advice'—Washington’s Farewell Address is filled with those types of warnings. You could go so far to say this is Washington’s 'advance notice’ of his ‘cautionary advice.’

Sir, I don’t know what you heard ⮐

But whatever it is, Jefferson started it

A brief moment of humor in what has been a very dour act. Consider it as a much needed laugh before shit hits the fan.

This is pretty historically accurate to Jefferson and Hamilton’s correspondence with George Washington. In one set of letters to both men, written by the president to discuss “internal tensions” in the administration, Jefferson wrote:

I have never tried to convince members of the legislature to defeat the plans of the Secretary of Treasury... I admit that I have, in private conversations, disapproved of the system of the Secretary of Treasury. However, this is because his system stands against liberty, and is designed to undermine and demolish the republic."

Meanwhile, Hamilton responded:

“I sincerely regret that you have been made to feel uneasy in your administration… though I consider myself the deeply injured party. I know that I have been an object of total opposition from Mr. Jefferson… that I have been the frequent subject of most unkind whispers by him. I have watched a party form in the Legislature, with the single purpose of opposing me.”

Basically, “I know I’ve been causing problems, but look what HE did!” Hamilton frequently objects to Washington’s paternal attitude toward him (as in “Meet Me Inside”), but here Alex sounds an awful lot like a sibling tattling to a parent. In “Cabinet Battle #2,” Jefferson taunts Hamilton to his face—referring to Washington as his father: “Daddy’s calling.”

Thomas Jefferson resigned this morning

Whatever you say, sir, Jefferson will pay for his behavior

Shh.

“Shh” has the connotation of silencing a child which implies a paternal relationship. This acts to convey the nature of the relationship between Washington and Hamilton.

Interestingly, the next time someone says “shh” is Hamilton speaking to Phillip in “Stay Alive (reprise)” following his shooting at the duel. This serves to further highlight the connection to paternal relationships.

Talk less

Washington is giving half of Burr’s repeated advice to “talk less, smile more.”

It makes sense that Washington would leave out Burr’s advice to “smile more” – Washington was constantly plagued with dental problems. By the time he became President, he was wearing false teeth. The idea of Washington’s wooden teeth is a myth. In fact, the President wore teeth made of “bone, hippopotamus ivory…brass screws, lead, and gold metal wire.”

He also may have worn dentures made of human teeth. His papers show that in 1784 he bought, “nine teeth from unidentified “Negroes”, possibly people enslaved at Mount Vernon.

Yet whatever Washington’s dentures were made out of, his teeth were a constant source of pain to him. That’s nothing to smile about.

A second meaning behind only reprising half of the line speaks to the difference between Washington’s understated manner and Burr’s craven manner. Washington lets others speak and make their points before he makes up his mind, but he does make decisions, such as at the end of “Cabinet Battle 2,” where he sides with Hamilton over Jefferson, but only after hearing them both out.

I’ll use the press

Hamilton was already known for his prolific writings, even though they were under pseudonyms in the press. He knew of the power of the press and the far reaching effects it would have on future American generations. As mentioned later in “The Adams Administration,” Hamilton was the founder of the New York Post, a publication which exists to this day.

Jefferson also used the press, forming a Democratic-Republican newspaper along with James Madison in 1791 known as the National Gazette, in response to the Federalist leanings of John Fenno’s Gazette of the United States.

I’ll write under a pseudonym

Alexander Hamilton wrote prolifically under pseudonyms – he wrote the Federalist Papers with John Jay and James Madison as Publius, and used other pseudonyms like Cato, Pacificus, Scipio, American Farmer, and Junius. A month after the Farewell Address was published, Hamilton made good on this promise when he attacked Jefferson as Phocion. Hamilton accused Jefferson of “having an affair” with one of his slaves – which was true.

On Hamilton’s pseudonyms, Chernow writes:

Hamilton seldom published under his own name and drew on a bewildering array of pseudonyms. Such pen names were sometimes transparent masks through which the public readily identified prominent politicians. The fashion of allowing anonymous attacks permitted extraordinary bile to seep into political discourse, and savage remarks that might not otherwise have surfaced appeared regularly in the press. The brutal tone of these papers made politics a wounding ordeal.

At one point in 1795, “The prolific Hamilton was now writing pseudonymous commentaries on his own pseudonymous essays.”

you’ll see what I can do to him—

Hamilton reportedly did privately unload on Jefferson after the resignation. According to his son, he said:

From the very outset, Jefferson had been the instigation of all the abuse of the administration and of the President; that he was one of the most ambitious and intriguing men in the community; that retirement was not his motive; that he found himself from the state of affairs with France in a position in which he was compelled to assume a responsibility as to public measures which warred against the designs of his party; that for that cause he retired; that his intention was to wait events, then enter the field and run for the plate; that if future events did not prove the correctness of this view of his character, he [Hamilton] would forfeit all title to a knowledge of mankind.

Hamilton was damn right that Jefferson was gonna come back and make a run for it. He was really good at reading people’s plans, most of the time.

I need you to draft an address

Hamilton wasn’t the only person to draft this address first it was Madison as said in the original one last ride “Madison wrote the first draft it’s a mess”. When Hamilton took over he was helped by none other then his wife Eliza!

Lin-Manuel Miranda – One Last Ride @Lin_Manuel

Yes! He resigned. You can finally speak your mind—

Hamilton was prone to immediate reactions to any perceived slight, and Miranda is capturing this personality trait here. While Hamilton may not have asked Washington to make an address in this particular instance, he had done it other times, such as when he was attacked by Gov. George Clinton:

This man born without honor was exceedingly

sensitive to any slights to his political honor. As an outsider on the American scene,

he did not believe that he could allow such slander to go unanswered, so he appealed

to Washington to correct the distortion: “This, I confess, hurts my feelings,

and if it obtains credit will require a contradiction,”

No, he’s stepping down so he can run for President

Miranda compresses the timeline a bit here for dramatic effect. Jefferson stepped down at the end of 1793, and the next presidential election was in 1796. In public, Jefferson claimed he resigned so he could retreat into his pastoral scholarly life at Monticello. In private, it was clear that he resigned out of frustration with Hamilton’s influence (see “Washington On Your Side”) and a belief that he could better build influence outside of the Cabinet.

As Chernow’s book portrays it, the roles here were reversed: Hamilton was the one who saw Jefferson’s resignation as positioning himself to become president:

When Hamilton’s son John wrote his father’s biography, he left out one story that is contained in his papers. The authenticity of the anecdote cannot be verified, but it jibes with other things Hamilton said. According to this story, soon after Jefferson announced his plans to step down, Washington and Hamilton were alone together when Jefferson passed by the window. Washington expressed regret at his departure, which he attributed to his desire to withdraw from public life and devote himself to literature and agriculture. Staring at Washington with a dubious smirk, Hamilton asked, “Do you believe, Sir, that such is his only motive?” Washington saw that Hamilton was biting his tongue and urged him to speak. Hamilton explained that he had long entertained doubts about Jefferson’s character but, as a colleague, had restrained himself. Now he no longer felt bound by such scruples. Hamilton offered this prediction, as summarized by his son:

From the very outset, Jefferson had been the instigation of all the abuse of the administration and of the President; that he was one of the most ambitious and intriguing men in the community; that retirement was not his motive; that he found himself from the state of affairs with France in a position in which he was compelled to assume a responsibility as to public measures which warred against the designs of his party; that for that cause he retired; that his intention was to wait events, then enter the field and run for the plate; that if future events did not prove the correctness of this view of his character, he [Hamilton] would forfeit all title to a knowledge of mankind.

Ha. Good luck defeating you, sir

I’m stepping down. I’m not running for President

The importance of Washington’s multiple decisions to step away from power cannot be overstated. Throughout history, many Republican revolutions have ended with military dictatorship. For example, as Washington was stepping away, Napoleon Bonaparte was on the rise in France. (In the year this speech was given–1796–Napoleon was invading Italy.) In exile on Elba, Napoleon is said to have lamented, “They wanted me to be another Washington.”

History would be very different if George Washington didn’t see the benefit of teaching us to say goodbye.

I’m sorry, what?

This line is spoken flatly and has no musical accompaniment. The total break from musicality is used to emphasize Hamilton’s shock. This also really highlights the truly incredible decision George Washington made in stepping down. Even Hamilton, the guy who is always ten steps ahead of everyone else, didn’t foresee this. This calls back to Jefferson’s taunt that Hamilton “nothing without Washington behind [him]”, another blow to Hamilton’s confidence.

It’s also a bit of breaking the fourth wall, since we’re losing a major character of the show, one of only a few to carry over between Act I and Act II. To have this happen without any foreshadowing or forcing of Washington out is a shock to the audience as well as Hamilton.

This same technique was used in the reprise of “The Story of Tonight” when Hamilton learns Burr is seeing a woman married to a British officer.

One last time

In Act 1, Hamilton says “one more time” to Washington; in Act 2, Washington says “one last time” to Hamilton. This could represent Hamilton’s hesitation to saying goodbye to Washington, and Washington’s optimistic attitude for the future, despite having to say goodbye one last time.

[WASHINGTON]

Your wife needs you alive, son, I need you alive!

[HAMILTON]

Call me son one more time!

Relax, have a drink with me

Let’s take a break tonight

A direct callback to the song of the same name, “Take a Break,” where Eliza and Angelica begged Alexander to go upstate with them for the summer. His refusal there and reluctance here hint at Hamilton’s obsession with work and inability to relax (he is non-stop).

And then we’ll teach them how to say goodbye

Washington’s retirement set a precedent of presidents serving for two terms only. This was only broken in 1940 by Franklin D. Roosevelt, who died during his fourth term after serving for 12 years and 39 days. Despite—or perhaps because of—this successful exception to the unwritten rule, a Constitutional amendment was finally passed to enshrine the two-term convention into law.

Washington also started the still-running tradition of a Farewell Address from all outgoing American Presidents; teaching them how to say goodbye. The Farewell Address has become a chance for Presidents, no longer worried about political pursuits, to speak their mind about their time in office.

This line gets called back during Hamilton’s soliloquy in “The World Was Wide Enough.” Hamilton sees Washington on the other side and asks him to “teach [him] how to say goodbye.”

To say goodbye ⮐

You and I

Washington has taken Hamilton under his wing throughout the play at this point, and Washington really wants to drive the point home that they’re a team. Almost a “you and me against the world” type thing.

Even though only Washington is resigning, in a way he’s ending both their political careers here. Like Jefferson said, Hamilton is ‘nothing’ without Washington behind him. And as we see once Washington leaves, Hamilton’s support network falls apart. Washington must have been aware that dissolving their partnership would have adverse affects on Hamilton. So in a way, the speech they both wrote could be considered ‘goodbye’ from both of them.

No, sir, why?

The President is about to give this guy $10 to buy a clue. Poor Hamilton. Here we see Washington working double time to rein Hamilton in and redirect him in more productive ways. Hamilton is losing that critical support.

Hamilton believed that staying in office for an extended period of time would make the officeholder be better at their work. Hamilton was probably shocked that Washington was going to let some noob run the country instead of the Continental Commander and two-term president.

I wanna talk about neutrality

This is a topic Washington touched on in his Farewell Address:

After deliberate examination, with the aid of the best lights I could obtain, I was well satisfied that our country, under all the circumstances of the case, had a right to take, and was bound in duty and interest to take, a neutral position. Having taken it, I determined, as far as should depend upon me, to maintain it, with moderation, perseverance, and firmness.

with Britain and France on the verge of war

As King George III complains about in “What Comes Next.”

Chernow notes that Hamilton disagreed with Washington’s neutral stance:

As its centerpiece, the farewell address called for American neutrality, shorn of names and party labels. Hamilton’s words, however, were saturated with arguments to promote the Jay Treaty. Beneath its impartial air, the farewell address took dead aim at the Jeffersonian romance with France.

I want to warn against partisan fighting

From Washington’s Farewell Address:

Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight), the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

But

This is also one of the first times where Washington out-rights ignores Hamilton. No waiting, no pausing for him to speak. Washington has made up his mind and Hamilton cannot influence it.

Hamilton is also probably thinking of all the possible scenarios to come out of his resignation, hence just the “but”. Hamilton also knows this is going to happen, and just throws something in to establish he is there, despite Washington doing more talking for once.

Pick up a pen, start writing

Hamilton must really be in shock—he’s never needed an invitation to start writing before.

Chernow tells us that Hamilton did indeed help Washington write his farewell address. But Hamilton wrote two versions: one revising a previous draft written with the assistance of James Madison, one a new version written from whole cloth, in Hamilton’s normal, prolix style. Washington chose Hamilton’s speech, and together they worked it down into a form that could fit in the newspapers.

I wanna talk about what I have learned

The Farewell Address, rather than summing up Washington’s achievements, was full of advice for the future leaders of the young nation:

…A solicitude for your welfare which cannot end but with my life, and the apprehension of danger, natural to that solicitude, urge me, on an occasion like the present, to offer to your solemn contemplation, and to recommend to your frequent review, some sentiments which are the result of much reflection, of no inconsiderable observation, and which appear to me all-important to the permanency of your felicity as a people.

The hard-won wisdom I have earned

Being the first president, Washington had a lot of precedents to set. Along the way, he surely learned the efficient ways to handle the job.

He had to learn in his early 20s how to care for and maintain an entire estate while helping it grow at the same time.

He had dealt with plentiful amounts of setbacks during the French & Indian War, not to mention the fact he was the one that caused the tensions to burst between England and France, starting the war with the Fort Necessity debacle (look it up, it’s worth it).

Also among said self-admitted errors, there is also his tenure as a burgess in the Virginia House of Burgesses. He learned a lot of lessons not only in politics and finances, but he learned a lot about life. He wants these lessons passed on to the country he helped create.

Since he had no biological children to speak of and Martha’s children (that George helped raise, seeing as they were two and four when they wed) died before George was even President, he looked at the country as his own child.

As far as the people are concerned ⮐

You have to serve, you could continue to serve—

This reflects Hamilton’s belief that elected officials should serve as long as they can. This is the logic behind Supreme Court members serving for life today. The Hamilton Plan, which he proposed at the Constitutional Convention, was for senators and a “national governor” to be elected for life, although this plan was rejected by many as “an elective monarchy.”

Hamilton’s enemies used this prior opinion as evidence that he was aristocratic, almost a monarchist.

At the end of this verse, the rhythm ramps up as if Hamilton is starting to take away the conversation and convince him to stay President. In the next line however, Washington changes it back to the original beat, as if he’s standing by his decision, which he is.

The people will hear from me

And if we get this right

This echoes Washington’s line to Hamilton in “Guns and Ships”—“If we manage to get this right/They’ll surrender by early light.” Both examples of Washington playing a fatherly role, entreating the brasher Hamilton to join him in doing something the right way.

We’re gonna teach ‘em how to say ⮐

Goodbye ⮐

You and I—

Apart from showing the nation how to move on, Washington references Hamilton’s “skill with a quill”; Washington and Hamilton are going to give the country an unforgettable and unmatchable goodbye address.

George Washington set a precedent for presidents to serve only two terms, since at that time it wasn’t a law. Thus, he taught future presidents to say goodbye after two terms.

Mr. President,

Washington was still president at this point, so Hamilton does address him as such. However, he is also now aware of Washington’s intention to step down. Hamilton uses Washington’s title as a persuasive tactic and also in denial.

they will say you’re weak ⮐

⮐

[WASHINGTON] ⮐

No, they will see we’re strong

This is a beautiful example of the differences in character between these two men: Hamilton prefers bold acts of bravery and perseverance to prove strength, whereas Washington is more political and sees how the real strength can be demonstrated by stepping back.

It is also a beautiful example of their difference in views, and of Hamilton’s deep respect for Washington. Hamilton is worried that the people might think Washington is weak if he resigns—the focus of this comment is Washington. In stark contrast, Washington’s reply shifts the focus onto the people. His answer implies that the people will see that “we (they, the country—with its newly-found freedom and independence) are strong,” even without him at the helm.

Your position is so unique

As the head of the Revolutionary forces, one of the most prominent Founding Fathers, and first president, Washington occupies a unique place in history. Had he chosen to make a different decision (such as following Hamilton’s proposed plan for lifetime appointments), American government would be very different today.

So I’ll use it to move them along

Why do you have to say goodbye?

Here, Hamilton seems to break from political pleading to the president to a more personal point; with the terseness of their father-son dynamic, and Hamilton’s own past in mind…

If I say goodbye, the nation learns to move on

Washington points out a concern that the nation will not collapse when he dies, as he feared it would if he served until he died (as Hamilton is encouraging).

It outlives me when I’m gone

Another mention of the theme of legacy that pervades this musical, with a subtle nod to a personal motif of Washington’s.

It’s interesting to note that, since Washington died two years after resigning, he very likely would have died in office had he served a third term, setting an entirely different precedent.

Like the scripture says:

The song’s musical style changes dramatically at this moment, with hip hop and R&B elements dropped in favor of a more gospel-influenced arrangement. George Washington departs the hustle of the verbal battleground of politics, entering the timeless rest of both the afterlife and the American mythos.

The piano accompaniment in this particular passage is strongly evocative of that from 2Pac’s “Changes” (originally from “The Way It Is” by Bruce Hornsby and the Range), a song that was released after Shakur’s death and serves as a memorial to the influential rapper’s legacy. Similarly, the farewell address featured in this song secured Washington’s legacy as “father of his country”, establishing the tone and character of the presidency.

Coincidentally, 2Pac’s lyrics include the lines, “And although it seems heaven-sent / We ain’t ready to see a black president”. In this production, President George Washington, here quoting “heaven-sent” scripture, is played by a black man.

“Everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree ⮐

And no one shall make them afraid.”

“Under their vine and fig tree” is a phrase quoted in the Hebrew Scriptures in three different places: Micah 4:4, 1 Kings 4:25, and Zechariah 3:10.1. This particular scripture quote is Micah 4:4.

George Washington used this phrase in correspondence throughout his life, and one can find Washington reference it almost fifty times.

https://twitter.com/Lin_Manuel/status/646377988343377920

Perhaps his most famous use was at the close of his Letter to the Hebrew Congregation at Newport, Rhode Island, where Washington used the full phrase, extracted from scripture shared by Jews and Christians, to express his hope that Jews would flourish in America:

May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants — while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.

May the father of all mercies scatter light, and not darkness, upon our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in His own due time and way everlastingly happy.

They’ll be safe in the nation we’ve made

Here, Washington lives up to his title as the father of the nation. His sentiment is remarkably similar to “Dear Theodosia,” when Hamilton and Burr were both at their most paternal.

I’ll make the world safe and sound for you…

…will come of age with our young nation

We’ll bleed and fight for you, we’ll make it right for you

If we lay a strong enough foundation

We’ll pass it on to you, we’ll give the world to you"

I wanna sit under my own vine and fig tree

A moment alone in the shade

Washington’s wording evokes a deep weariness with fighting and governing after decades of public service. His home in Mount Vernon was nestled in a forest, so he is also betraying some homesickness here. ‘Shade’ can also refer to being out of the spotlight which he has been under for many years due to the war and presidency.

The use of ‘shade’ (particularly rhyming with ‘made’ above) is also reminiscent of Jefferson’s words in “Cabinet Battle #1”—“Don’t tax the South cuz we got it made in the shade”—again, linking Virginia to the shade and both to prosperity and its leisures.

This song has a couple of very Jeffersonian/Virginian motifs in it—the later “George Washington’s coming home” being the most obvious—signaling that Washington is allowing himself to be a little biased towards his home instead of holding back and staying neutral as he has done through the various cabinet debates of Act II.

At home in this nation we’ve made

Washington’s contemporaries were already mythologizing his decision to leave office for the sedate life of Mount Vernon.

They drew parallels with a legendary Roman figure named Cincinnatus, who left his farm in the middle of plowing the field, became a dictator to lead the Romans to victory, before giving up absolute power to go back to farming. The song uses farming and homesteading metaphors to emphasize Washington as a soldier-farmer of legend.

The U.S. city of Cincinnati was also named after Cincinnatus.

One last time

With this repetition of Washington’s refrain, Hamilton finally accepts Washington’s decision to step down.

The piano line here mimics the tune of Usher’s “There Goes My Baby” which could be the proud father instinct of George Washington finally imparting his last words of wisdom onto his country and Alexander.

[HAMILTON]

At this point, strings come in under Hamilton’s spoken recitation – a cello at first, then violins and other strings.

They play a variation on the “Story of Tonight” theme that becomes more and more recognizable, especially once it hits the “tomorrow they’ll be more of us” section.

Though, in reviewing the incidents of my administration, I am unconscious of intentional error, I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors. I shall also carry with me

Mostly verbatim from the final paragraphs of Washington’s Farewell Address, underscoring the gravity and significance of these words to the future of the young United States.

Hamilton recites the speech, Washington catches the thread and begins to sing along, until eventually the president’s melody soars movingly above the spoken word. This is a straight grab from will.i.am’s song “Yes We Can” in support of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign in 2008, which intertwines spoken and sung versions of a speech by Obama:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jjXyqcx-mYY

Interestingly, Hamilton is the one who speaks and Washington is the one that sings. This may be a way to illustrate that while Hamilton can draft an excellent, persuasive speech, it takes Washington’s heart and politic to animate it in a way that makes it truly accessible and moving. Chernow says: “their two voices blended admirably together. The result was a literary miracle.” This blending of “voices” is portrayed perfectly by their literal voices blending in the delivery of the address.

Lin-Manuel Miranda has confirmed that Washington raps only when he’s frustrated and forgets his stately place in history. In his final refrain in the show, he’s belting to the rafters. He’s at peace.

The hope (The hope) ⮐

That my country will ⮐

View them with indulgence; (View them with indulgence) ⮐

And that ⮐

After forty-five years of my life dedicated to its service with an upright zeal (After forty-five years of my life dedicated to its service with an upright zeal) ⮐

The faults of incompetent abilities will be ⮐

Consigned to oblivion, as I myself must soon be to the mansions of rest (Consigned to oblivion, as I myself must soon be to the mansions of rest) ⮐

I anticipate with pleasing expectation that retreat in which I (I anticipate with pleasing expectation that retreat in which I) ⮐

Promise myself to realize the sweet enjoyment of partaking (Promise myself to realize the sweet enjoyment of partaking) ⮐

In the midst of my fellow-citizens, the benign influence of good laws (In the midst of my fellow-citizens, the benign influence of good laws) ⮐

Under a free government, the ever-favorite object of my heart, and the happy reward, as I trust (Under a free government, the ever-favorite object of my heart, and the happy reward, as I trust) ⮐

Of our mutual cares, labors, and dangers (Of our mutual cares, labors, and dangers)

Mostly verbatim from the final paragraphs of Washington’s Farewell Address, underscoring the gravity and significance of these words to the future of the young United States.

Hamilton recites the speech, Washington catches the thread and begins to sing along, until eventually the president’s melody soars movingly above the spoken word. This is a straight grab from will.i.am’s song “Yes We Can” in support of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign in 2008, which intertwines spoken and sung versions of a speech by Obama:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jjXyqcx-mYY

Interestingly, Hamilton is the one who speaks and Washington is the one that sings. This may be a way to illustrate that while Hamilton can draft an excellent, persuasive speech, it takes Washington’s heart and politic to animate it in a way that makes it truly accessible and moving. Chernow says: “their two voices blended admirably together. The result was a literary miracle.” This blending of “voices” is portrayed perfectly by their literal voices blending in the delivery of the address.

Lin-Manuel Miranda has confirmed that Washington raps only when he’s frustrated and forgets his stately place in history. In his final refrain in the show, he’s belting to the rafters. He’s at peace.

George Washington’s going home!

These lines are a reprisal of the lines at the top of the act, “Thomas Jefferson’s coming home,” in “What’d I Miss” when the other man arrived back in Monticello before taking his place in the new American government. In Jefferson’s case, it’s a joyous welcome, and for Washington it’s a bittersweet farewell.

Washington, a fellow Virginian, gets to share the motif, though he instead ‘goes’ home to Mount Vernon, stepping down from governing. His time has ended, but Thomas Jefferson’s place is still with the government, as he is yet to become America’s third president.

He’s not just going home to Mount Vernon; he’s on his way to die, which, historically, will happen about a year and a half after he leaves the presidency. So it’s not a homecoming, it really is a “homegoing,” a funeral, fitting this song’s role as a eulogy.

Teach ‘em how to say goodbye

Hamilton finally telling Washington to “teach them how to say goodbye” shows Hamilton’s approval of Washington’s decision which was not present before.

George Washington’s going home

These lines are a reprisal of the lines at the top of the act, “Thomas Jefferson’s coming home,” in “What’d I Miss” when the other man arrived back in Monticello before taking his place in the new American government. In Jefferson’s case, it’s a joyous welcome, and for Washington it’s a bittersweet farewell.

Washington, a fellow Virginian, gets to share the motif, though he instead ‘goes’ home to Mount Vernon, stepping down from governing. His time has ended, but Thomas Jefferson’s place is still with the government, as he is yet to become America’s third president.

He’s not just going home to Mount Vernon; he’s on his way to die, which, historically, will happen about a year and a half after he leaves the presidency. So it’s not a homecoming, it really is a “homegoing,” a funeral, fitting this song’s role as a eulogy.

George Washington’s going home

These lines are a reprisal of the lines at the top of the act, “Thomas Jefferson’s coming home,” in “What’d I Miss” when the other man arrived back in Monticello before taking his place in the new American government. In Jefferson’s case, it’s a joyous welcome, and for Washington it’s a bittersweet farewell.

Washington, a fellow Virginian, gets to share the motif, though he instead ‘goes’ home to Mount Vernon, stepping down from governing. His time has ended, but Thomas Jefferson’s place is still with the government, as he is yet to become America’s third president.

He’s not just going home to Mount Vernon; he’s on his way to die, which, historically, will happen about a year and a half after he leaves the presidency. So it’s not a homecoming, it really is a “homegoing,” a funeral, fitting this song’s role as a eulogy.

Going home

Washington out.

George Washington’s going home

These lines are a reprisal of the lines at the top of the act, “Thomas Jefferson’s coming home,” in “What’d I Miss” when the other man arrived back in Monticello before taking his place in the new American government. In Jefferson’s case, it’s a joyous welcome, and for Washington it’s a bittersweet farewell.

Washington, a fellow Virginian, gets to share the motif, though he instead ‘goes’ home to Mount Vernon, stepping down from governing. His time has ended, but Thomas Jefferson’s place is still with the government, as he is yet to become America’s third president.

He’s not just going home to Mount Vernon; he’s on his way to die, which, historically, will happen about a year and a half after he leaves the presidency. So it’s not a homecoming, it really is a “homegoing,” a funeral, fitting this song’s role as a eulogy.

History has its eyes on you

A reference to Washington’s first act reminder to Hamilton. Here, the eyes of history are on Washington as he turns down the promise of endless power. Some historians suggest that one of the reasons that Washington stepped down was his consciousness of the eyes of history; he knew democracy, and the presidency, could not survive without a peaceful transition.

In some performances, Christopher Jackson gestures expansively towards the audience as he delivers this line, suggesting that Washington may be referring to the American “grand experiment” in general, and what the people will do with the opportunity before them.

George Washington’s going home

These lines are a reprisal of the lines at the top of the act, “Thomas Jefferson’s coming home,” in “What’d I Miss” when the other man arrived back in Monticello before taking his place in the new American government. In Jefferson’s case, it’s a joyous welcome, and for Washington it’s a bittersweet farewell.

Washington, a fellow Virginian, gets to share the motif, though he instead ‘goes’ home to Mount Vernon, stepping down from governing. His time has ended, but Thomas Jefferson’s place is still with the government, as he is yet to become America’s third president.

He’s not just going home to Mount Vernon; he’s on his way to die, which, historically, will happen about a year and a half after he leaves the presidency. So it’s not a homecoming, it really is a “homegoing,” a funeral, fitting this song’s role as a eulogy.

We’re gonna teach ‘em how to

Say goodbye! (Say goodbye!)

The repetition of the Company’s “Say goodbye” conveys that George Washington has succeeded in his efforts to teach the people how to say goodbye and move on from his presidency.

It may also be seen as an imperative, smuggled past the fourth wall, telling the audience to say goodbye to the character of George Washington as this is his final appearance until “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story”, when he appears only to lead the company in a ghostly recitation of the song’s title.

Say goodbye!

In this line, we’re not only saying goodbye to Washington, but we’re also saying goodbye to Hamilton’s mentor. Miranda states that “Washington is Dr. Dre to Hamilton’s Eminem,” which is true. As soon as Washington steps down, all Hell breaks loose, and the “fall” part of Hamilton’s rise and fall story steepens deeply, especially as seen in the tracks one after this. As Jefferson said, Hamilton is nothing without Washington behind him. The E-Brake to a speeding car. Remove it, a crash results.

One last time!

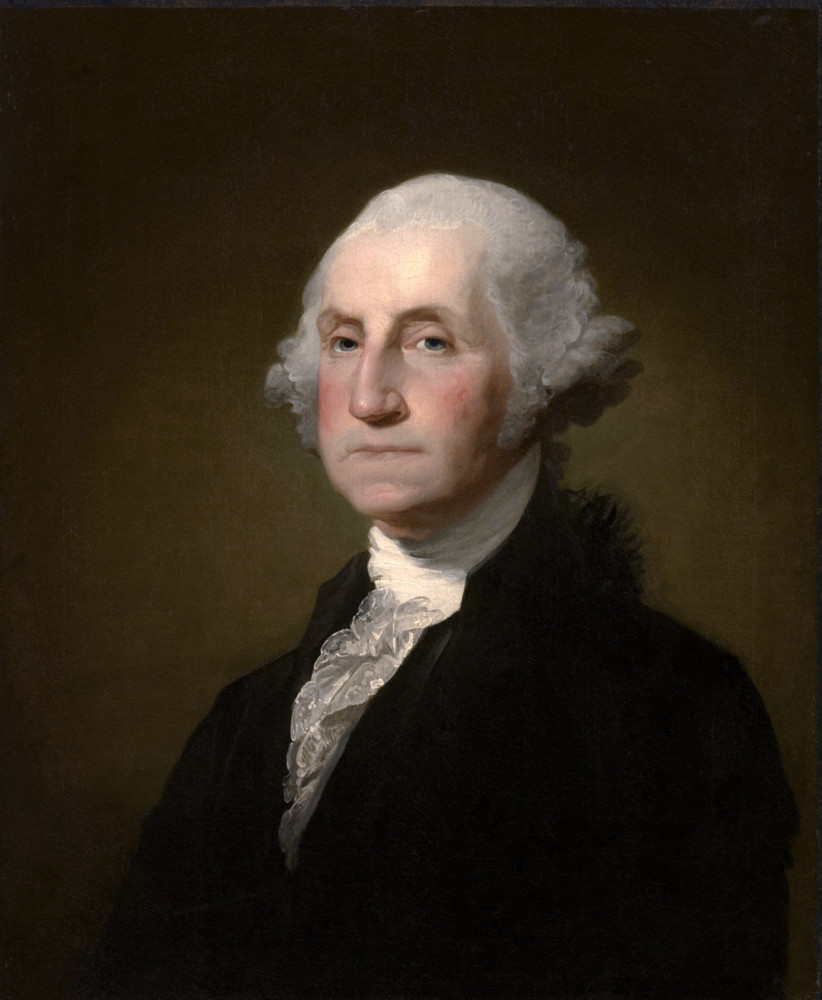

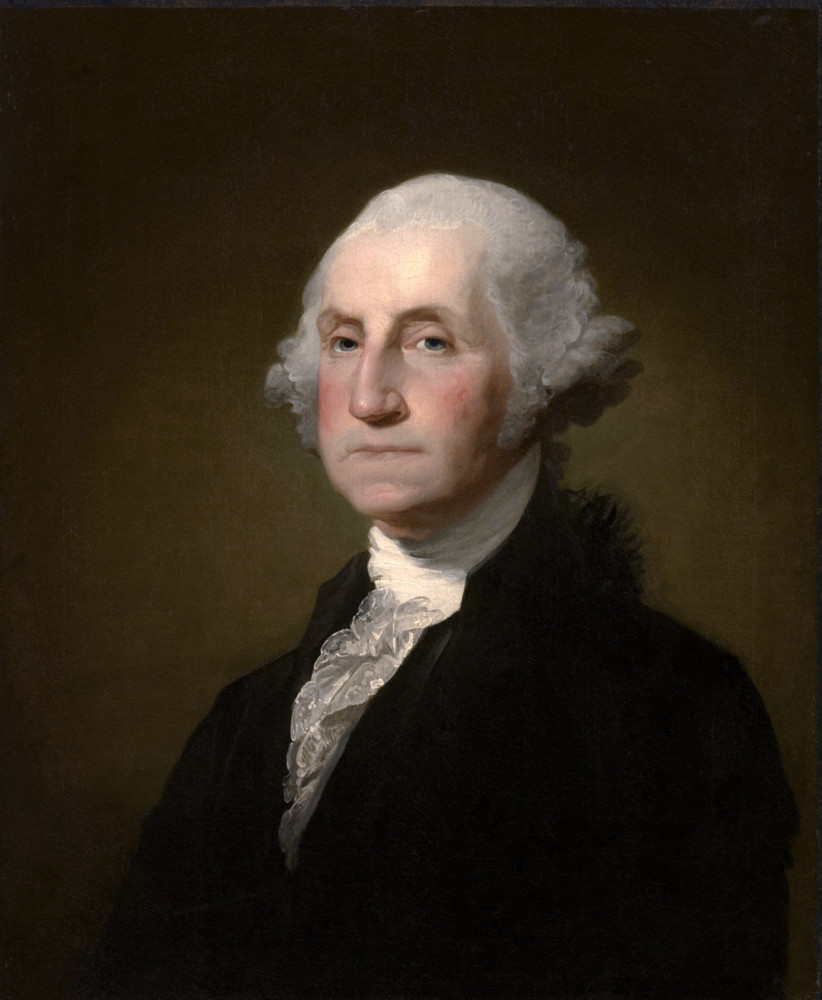

As he says his final “one last time” in the Broadway play, Washington stretches out his arm in a classic oratorical manner. Audience members may be struck by a sense of familiarity upon seeing this pose.

Though it may be a coincidence, this may be a reference to one of the most famous paintings of Washington, known as the Landsdowne Portrait. This portrait, painted in 1796, depicts Washington renouncing his opportunity for a 3rd term as President- precisely the timing and subject matter of this song.

(One last time!)

There’s some similarity here between the last note of this song and the last note of “When You’re Home,” from Miranda’s other musical In the Heights. The actor who plays Washington, Christopher Jackson, was also in In the Heights.

In “When You’re Home,” Jackson’s character is welcoming someone home. In “One Last Time,” Washington is saying goodbye and going home.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u1wLGAqWV8A#t=1m05s