Back to Hamilton: An American Musical (Original Broadway Cast Recording)

Dear Theodosia

Lin-Manuel Miranda & Leslie Odom, Jr.

Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton both had children very soon after the Revolutionary War. Here they take a moment to coo, and to realize the human element of the country they are just beginning to build. The song again brings up the similarities in their lives—their orphanhoods, their Revolutionary war experiences, their parenthoods, and their desire to take part in laying “a strong enough foundation” in the new United States.

Both Lin-Manuel Miranda and Alex Lacamoire, the show’s music director, included songs on their HAMthology playlists by The Decemberists that seem to have influenced the loving quality and sweet, lullaby-like tone of this song. Miranda picked “Red Right Ankle,” and Lacamoire chose “June Hymn”—the second’s influence is particularly recognizable. Some would argue the song’s melody is also reminiscent of “Hey There Delilah.”

Lin-Manuel Miranda’s first child was born in 2014, only a few months before the show opened off-Broadway. He’s gotten a lot of credit for writing such a lovely father-child lullaby in honor of his son. However, the truth is the song honors a different member of the Miranda family, and here he explains why:

Dear Theodosia, what to say to you? ⮐

You have my eyes. You have your mother’s name

Aaron Burr married Theodosia Bartow Prevost in 1782. Prevost was nearly 10 years his senior and already the mother of several children. They had a daughter, also named Theodosia, in 1783. Nicknamed “Theo” by her family, she was the only one of their children to survive to adulthood.

The elder Theodosia died of stomach cancer in 1794. Young Theodosia was not quite eleven years old. During the show’s Off-Broadway run, this was the subject of a reprise in Act II, but it was cut from the show during its transition to Broadway reportedly because of the audience’s confusion of Burr’s wife and daughter (who were both named Theodosia).

Burr did not remarry for nearly forty years. He insisted that “The mother of my Theo was the best woman and finest lady I have ever known.”

When you came into the world, you cried and it broke my heart

I’m dedicating every day to you

Burr was true to his word, and seems to have taken Angelica’s words in “The Schuyler Sisters” to heart. He raised his daughter with all of the privilege and formal education that would usually only be given to sons. In life, Theodosia “Theo” Burr was acknowledged to be accomplished in the feminine arts of French, music, and dancing, as well as the more restricted male spheres of arithmetic, Latin, and Greek. Burr personally supervised her education and they kept up a rigorous correspondence throughout her life.

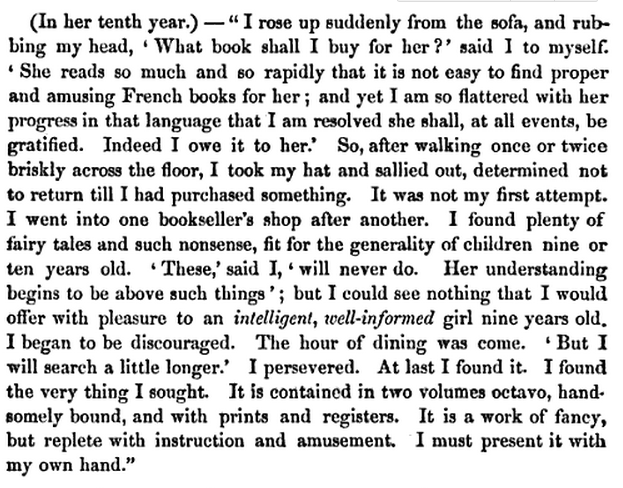

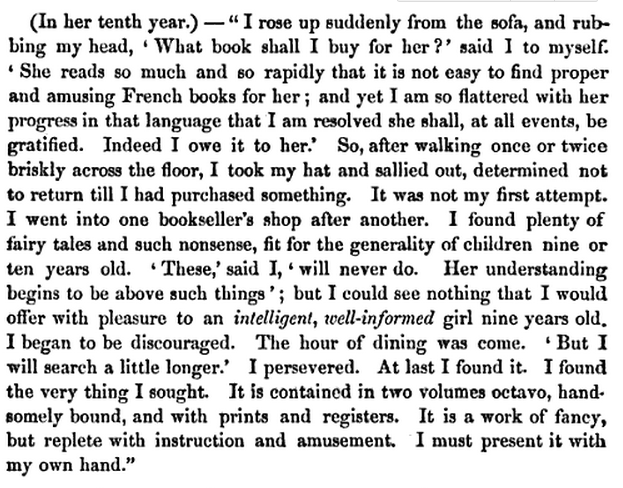

For an example of this correspondence, see this letter from Burr to Theodosia in which he discusses the trouble he goes through to find just the right book for her:

Domestic life was never quite my style

Theodosia’s mother, of the same name, died when she was ten years old. After her mother died Aaron Burr also took up the lessons her mother would have supervised, teaching her social graces and the hostess’s arts.

When you smile

Smiling is one of the first things that babies learn to do, and seeing that smile warms the heart of every parent.

But, of course, smiling also means something peculiar to Burr, whose “talk less, smile more” mantra means that his smile is usually calculated. Burr’s smile is associated with conceding defeat, repressing thoughts or opinions, or being satisfied enough to wait instead of act.

In contrast to all of that, Theodosia’s smile is purely due to genuine happiness, which is why Burr is so thrown by it, and, if one takes the cut reprise into account, it later becomes the reason he tries to get ahead.

you knock me out, I fall apart

And I thought I was so smart

Burr considers himself to be a very smart man, and for good reason, but Theodosia is a revelation to him. The things he learned about the world and about himself, with the arrival of her birth, wouldn’t have been something he could have learned in books. He’s gained a new kind of knowledge and wisdom.

Whatever can be said of Burr’s pride and arrogance all fades out when he sees his daughter smile. Despite his flaws and shortcomings, his love for his daughter shows the audience that Burr is human and is relatable to modern day people.

Because everyone knows how the story ends (Burr kills Hamilton), Miranda struggled to sympathize the audience with Burr. “Dear Theodosia” is one of the key songs in Hamilton that helps the audience sympathize with the show’s antagonist.

You will come of age with our young nation ⮐

We’ll bleed and fight for you, we’ll make it right for you ⮐

If we lay a strong enough foundation ⮐

We’ll pass it on to you, we’ll give the world to you

The first generation of Americans had a bright world in front of them, but little suffering to claim:

They were not soldiers or sufferers. They did not know British oppression or the conditions of colonial society. The Revolution was a gift of their parents, and their task was to make something of it.

Thomas Paine’s The Crisis, which Washington ordered read to his soldiers at Valley Forge, also invoked the idea that the Revolution would give American children a better life:

I once felt all that kind of anger, which a man ought to feel, against the mean principles that are held by the Tories: a noted one, who kept a tavern at Amboy, was standing at his door, with as pretty a child in his hand, about eight or nine years old, as I ever saw, and after speaking his mind as freely as he thought was prudent, finished with this unfatherly expression, “Well! give me peace in my day.” Not a man lives on the continent but fully believes that a separation must some time or other finally take place, and a generous parent should have said, “If there must be trouble, let it be in my day, that my child may have peace;” and this single reflection, well applied, is sufficient to awaken every man to duty.

And you’ll blow us all away… ⮐

Someday, someday

This foreshadows Philip’s number, Blow Us All Away, introducing the idea that someday (in the second act), Burr and Hamilton expect their children to grow up and play important roles.

Yeah, you’ll blow us all away

This theme comes back in Blow Us All Away when Philip is an adult and about to duel George Eacker. It also applies tragically to Theodosia; as she died when her ship was lost at sea during a storm at age 29.

Oh Philip, when you smile I am undone ⮐

My son ⮐

Look at my son. Pride is not the word I’m looking for

The Hamiltons' first son, Philip, was born in 1782.

Hamilton was by all accounts a doting father. From one of two surviving letters to Philip:

For I know that you can do a great deal, if you please, and I am sure you have too much spirit not to exert yourself, that you may make us every day more and more proud of you.

There is so much more inside me now

Hamilton, in a letter to a friend in 1782:

You cannot imagine how entirely domestic I am growing. I lose all taste for the pursuits of ambition, I sigh for nothing but the company of my wife and my baby. The ties of duty alone or imagined duty keep me from renouncing public life altogether. It is however probable I may not be any longer actively engaged in it.

This attitude, however, is short-lived. Indeed, Alexander doesn’t even make it through another song—namely, “Non-Stop”— before he is once again prioritising his career and the nation over his family, and this trend continues into Act II, with “Take a Break”. Indeed, it is only with his political demise and Philip’s death towards the end of the musical that, in “It’s Quiet Uptown”, Hamilton finally puts his family first.

For all that, the cast recording isn’t entirely fair to Hamilton by showing us this sudden reversal; in the show an interlude between this and the subsequent song, entitled “Tomorrow There’ll Be More of Us”, provides a tragic explanation for his breakneck pace from here on out.

Oh Philip, you outshine the morning sun ⮐

My son ⮐

When you smile, I fall apart ⮐

And I thought I was so smart

A play on words that has been a favorite of playwrights going back at least to Shakespeare’s Richard III—“Now is the winter of our discontent made glorious summer by this sun of York”—and probably further.

The use of “son” as a homophone for “sun” could refer to how Hamilton’s life revolves around the Philip, just as the earth revolves around the sun.

It may also be a (somehow positive) nod to Hamilton’s various moments of comparison to Icarus. Philip is the shining sun that makes his wings and his grand plans fall apart. Sadly, this does end up coming true as Hamilton lets go of much of his ambition after Philip’s death in Act II.

Also notable is how simple this rhyme is when compared to the complicated rhyme schemes Hamilton constructs in songs like “My Shot.” This breakdown regularly occurs whenever he is feeling particularly emotional and distracted. See its first appearance in “Aaron Burr, Sir,” when he breaks up several lines of consistently rhyming couplets with the suddenly awkward, “He looked at me like I was stupid / I’m not stupid,” or its much more obvious recurrence later in “It’s Quiet Uptown,” where he barely bothers to rhyme at all.

My father wasn’t around ⮐

[BURR] ⮐

My father wasn’t around

Hamilton’s line acknowledges that his father was essentially a “deadbeat dad,” a common issue in hip-hop culture. Alexander reached out to his father, James, many times in his adult life, and even invited him to come live with the Hamilton family in New York. James declined the offer.

Burr, meanwhile, was a true orphan. He was raised by his uncle, Timothy Edwards.

Lin-Manuel Miranda, like many other storytellers, is really into exploring the lives and psychologies of orphans. His main character in In The Heights, Usnavi, was also an orphan. See that show’s “Hundreds of Stories,” when Usnavi sings that his folks “left me on my own.”

I swear that ⮐

I’ll be around for you

Hamilton, in a letter to a friend in 1782:

You cannot imagine how entirely domestic I am growing. I lose all taste for the pursuits of ambition, I sigh for nothing but the company of my wife and my baby. The ties of duty alone or imagined duty keep me from renouncing public life altogether. It is however probable I may not be any longer actively engaged in it.

This attitude, however, is short-lived. Indeed, Alexander doesn’t even make it through another song—namely, “Non-Stop”— before he is once again prioritising his career and the nation over his family, and this trend continues into Act II, with “Take a Break”. Indeed, it is only with his political demise and Philip’s death towards the end of the musical that, in “It’s Quiet Uptown”, Hamilton finally puts his family first.

For all that, the cast recording isn’t entirely fair to Hamilton by showing us this sudden reversal; in the show an interlude between this and the subsequent song, entitled “Tomorrow There’ll Be More of Us”, provides a tragic explanation for his breakneck pace from here on out.

(I’ll be around for you)

Burr wrote prolifically to his wife and daughter when he was called away to Philadelphia for work. In a letter to his nine-year-old Theodosia in 1793:

In looking over a list made yesterday (and now before me), of letters of consequence to be answered immediately, I find the name of T. B. Burr. At the time I made the memorandum I did not advert to the compliment I paid you by putting your name in a list with some of the most eminent persons in the United States. So true is it that your letters are really of consequence to me.

Burr’s promise comes to haunt him during his duel—he outright states in “The World Was Wide Enough” that he doesn’t want his daughter to become an orphan.

I’ll do whatever it takes

Comparing this to Burr’s subsequent line, “I’ll make a million mistakes”, it is interesting to see what each father promises to their child and how it reflects on their personal belief systems.

Hamilton says how he will do whatever it takes, showing Hamilton’s brash personality and how he is willing to “always say what he believes”.

Burr says how he will make a million mistakes, showing Burr’s cautious, calculated, and almost wish-washy stance on ideas and how he will “wait here and see which way the wind will blow”.

I’ll make a million mistakes

Throughout the play, Hamilton criticizes Burr for having no beliefs, but his daughter is the one thing Burr ultimately does stand for. His love for her is what drives him to finally succeed when the stakes are highest—the duel against Hamilton. In “The World Was Wide Enough,” despite his rage at Hamilton “poison[ing] his political pursuits,” Burr says right before firing his winning shot:

“I had only one thought before the slaughter:

This man will not make an orphan of my daughter”

But his success is bittersweet—he instantly regrets it.

I’ll make the world safe and sound for you…

These lines are ironic as Philip dies defending his father’s honor in a duel at nineteen. Theodosia was lost at sea at twenty-nine. She had been on her way to see her father, who had just returned from four years of exile in Europe. Both men end up outliving their children, which is what makes these lyrics so ironic.

…will come of age with our young nation

We’ll bleed and fight for you, we’ll make it right for you

Throughout the play, Hamilton criticizes Burr for having no beliefs, but his daughter is the one thing Burr ultimately does stand for. His love for her is what drives him to finally succeed when the stakes are highest—the duel against Hamilton. In “The World Was Wide Enough,” despite his rage at Hamilton “poison[ing] his political pursuits,” Burr says right before firing his winning shot:

“I had only one thought before the slaughter:

This man will not make an orphan of my daughter”

But his success is bittersweet—he instantly regrets it.

If we lay a strong enough foundation ⮐

We’ll pass it on to you, we’ll give the world to you

These lines are ironic as Philip dies defending his father’s honor in a duel at nineteen. Theodosia was lost at sea at twenty-nine. She had been on her way to see her father, who had just returned from four years of exile in Europe. Both men end up outliving their children, which is what makes these lyrics so ironic.

And you’ll blow us all away... ⮐

Someday, someday ⮐

Yeah, you’ll blow us all away ⮐

Someday, someday

Theodosia died in a storm at sea, and Philip was fatally shot in a duel (depicted later in “Blow Us All Away”). In a sense, both were literally or figuratively blown away in the prime of life, instead of surviving to inherit the world their fathers hoped to build for them. Even a sweet and tender song like this one must have its note of irony.

These last lines sung by Hamilton and Burr are the only lines in the song that are sung in unison, reflecting the only thing they agree upon and share: their love for their children.